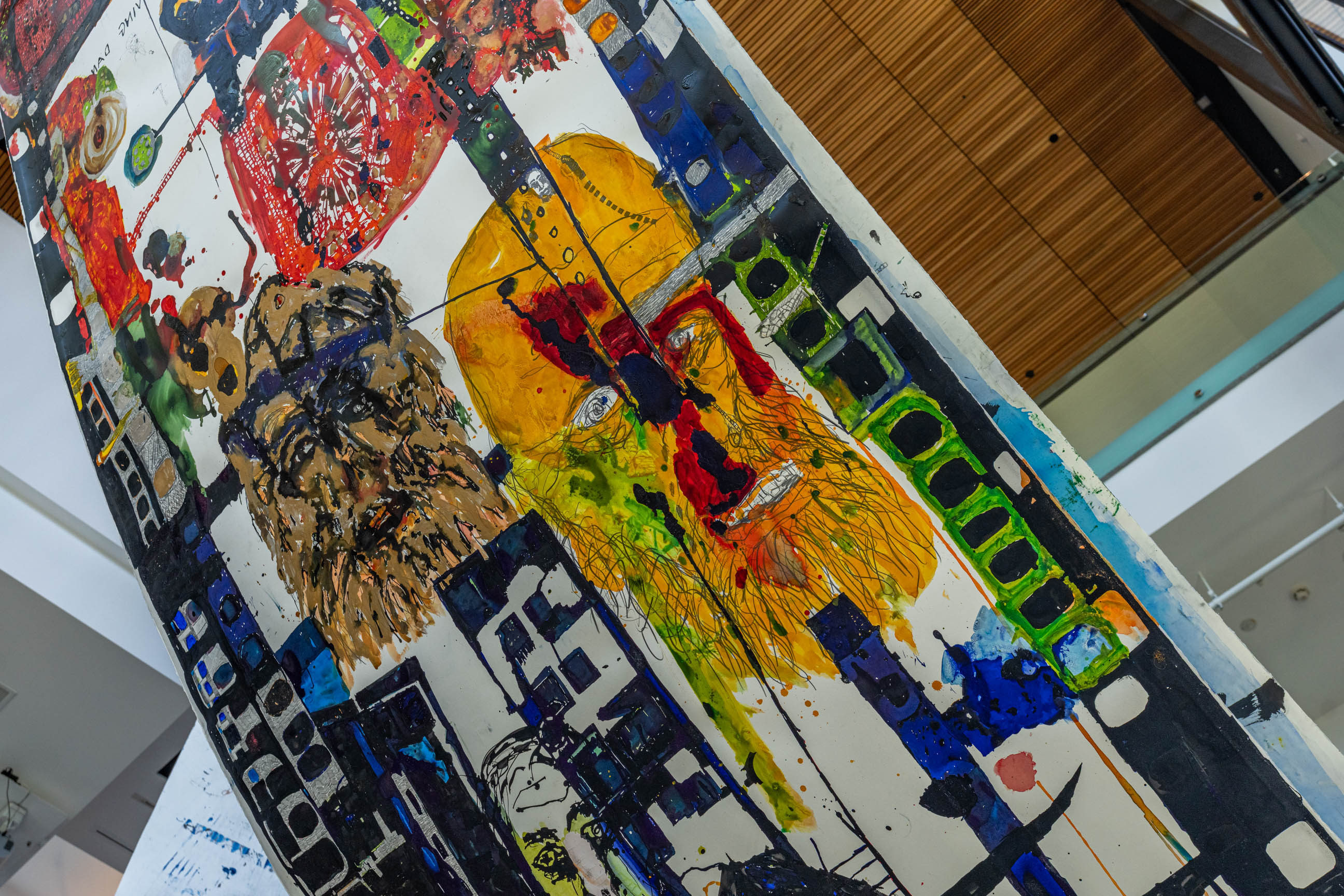

TO BEAR WITNESS

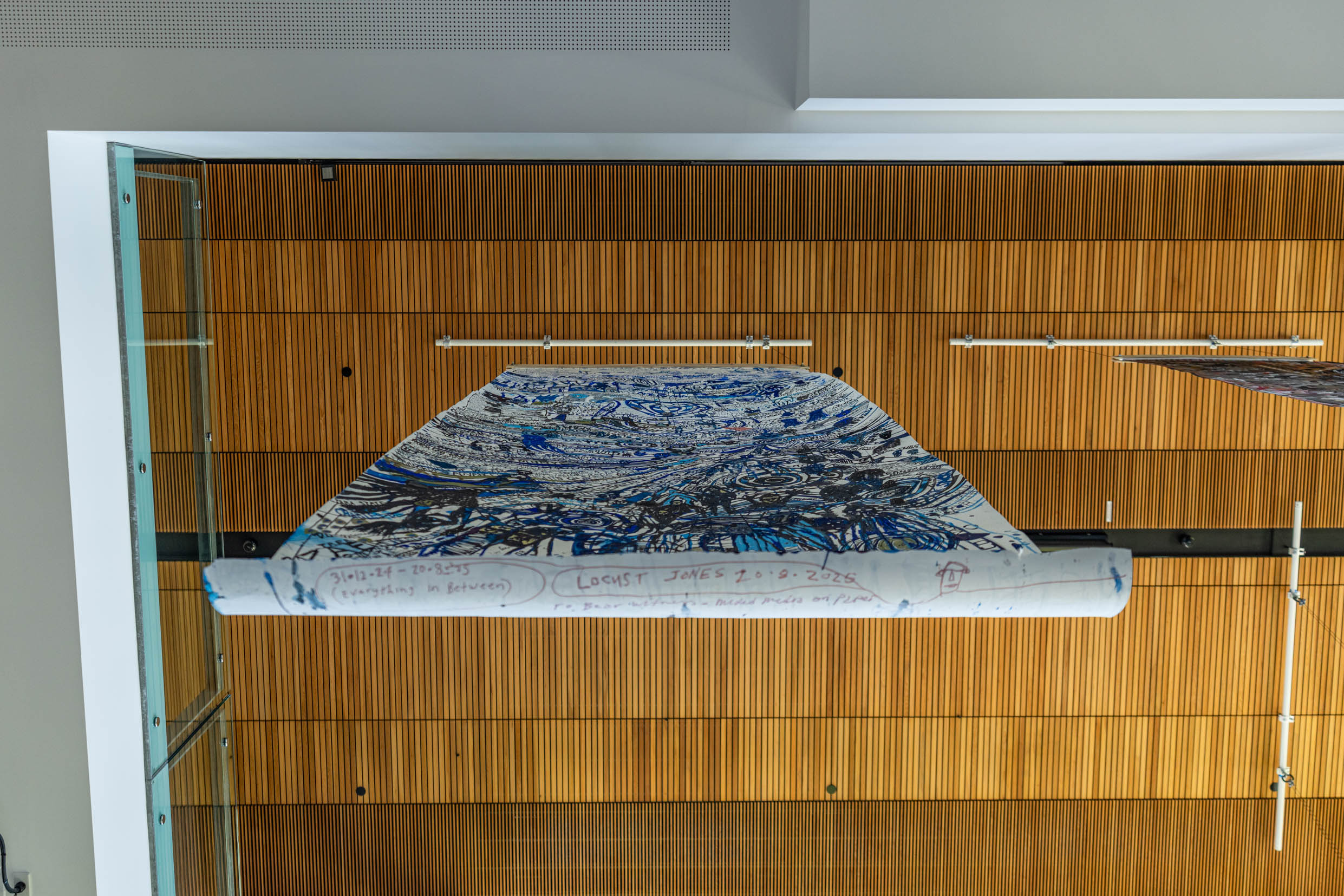

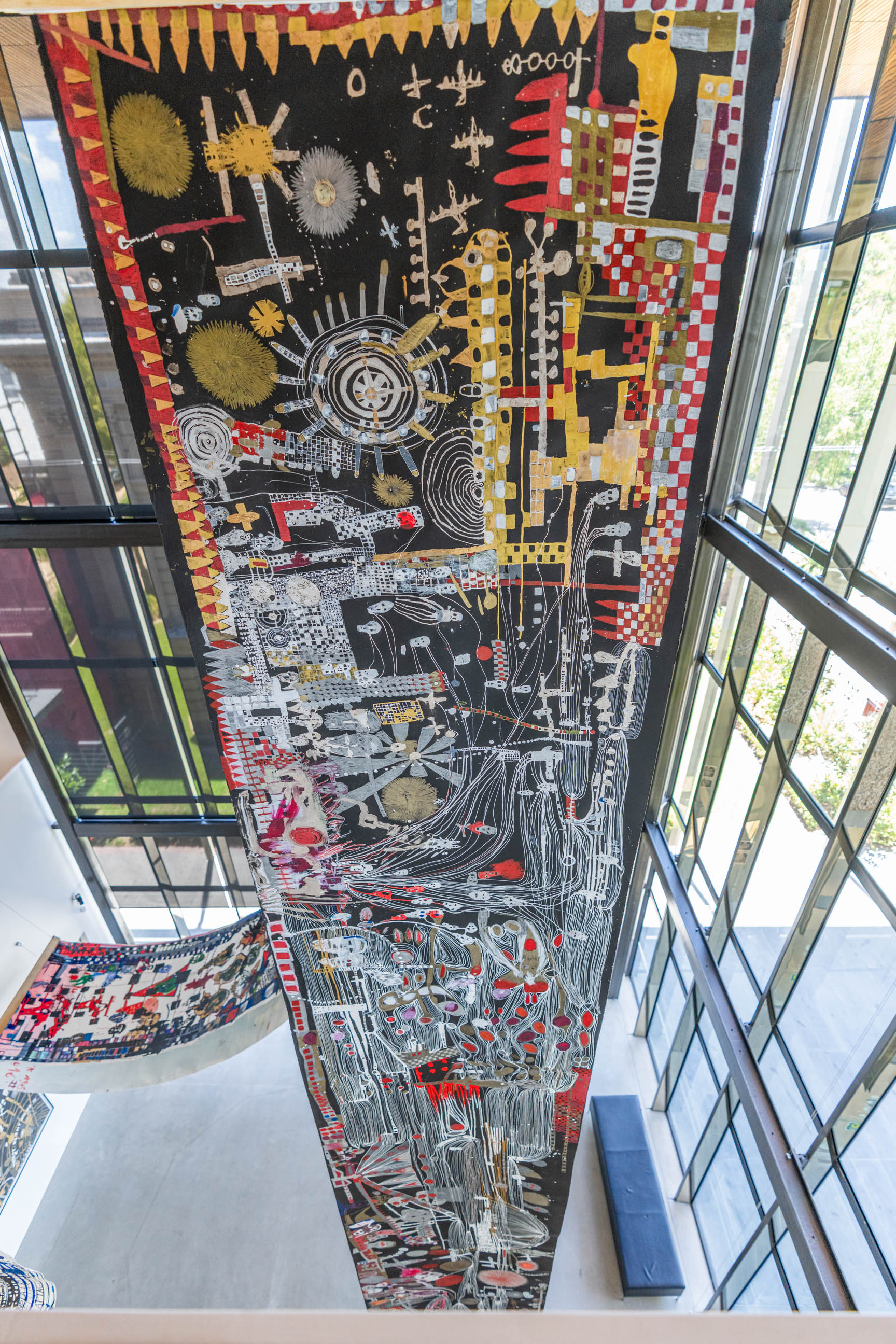

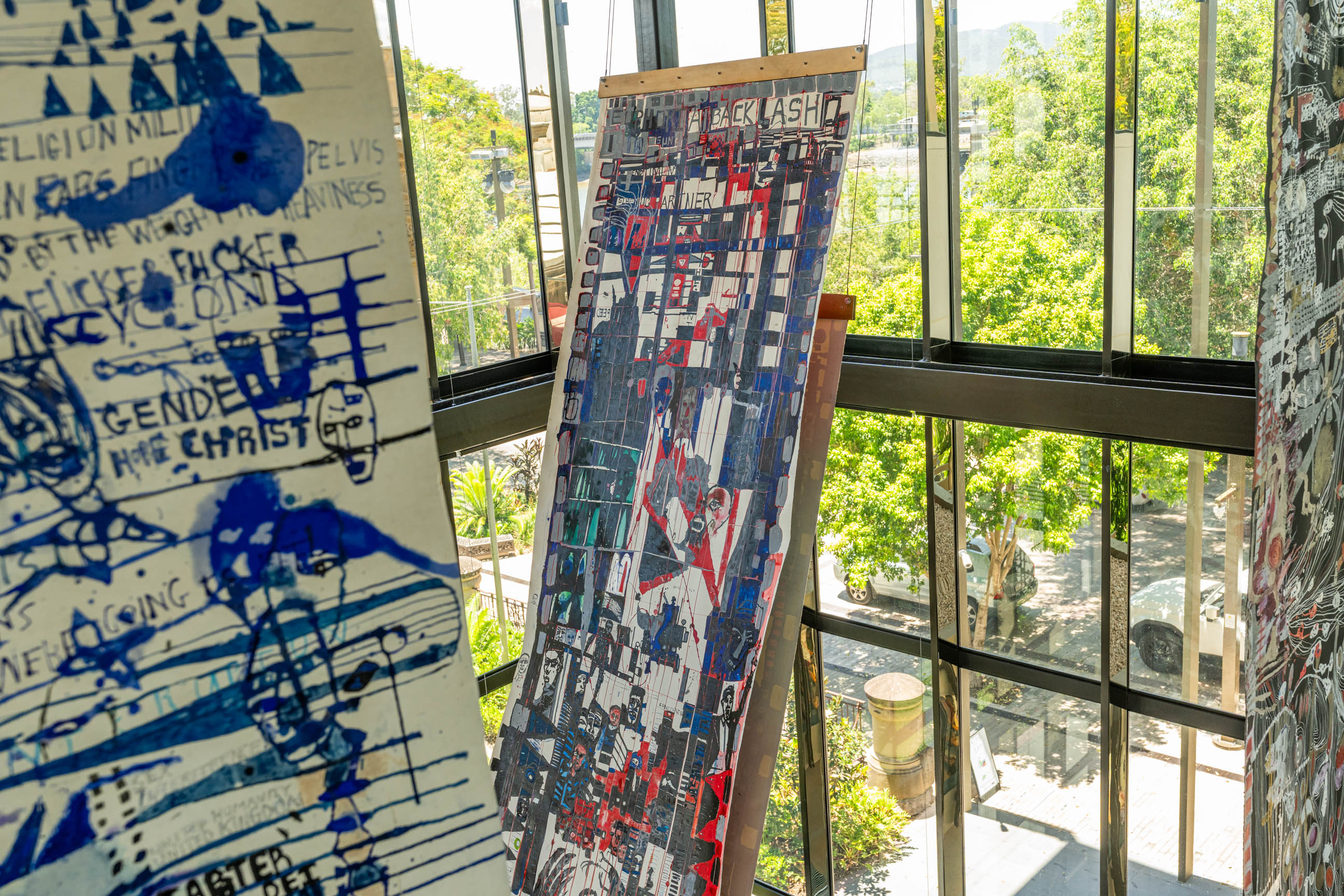

For over 20 years, Locust's practice has woven layers of stories and images that replicate the frenetic pace at which society consumes everyday news and current affairs, in a variety of mediums. To Bear Witness will feature large scale vertical drawings cascading through RMOA’s Atrium Gallery.

Locust Jones: Harrowing

Locust Jones was sixteen when he went to work on the neighbour’s farm. His job was to tow the harrow behind the tractor. In tilling a plough’s blade breaks open the field, the harrow then follows the same path to break up clumps and even things out. Despite this task of refinement, harrows are brutal devices. Some have spikes arrayed on a rigid frame like a huge bed of nails aimed faced down. The one Jones towed was nearly four meters wide. It hugged the ground with heavy steel rods that chain-linked into a frame and sharpened up for spikes. The farmer warned him not to turn too tightly, but he was young and didn’t pay attention. The harrow climbed up a rear wheel, took out the mud guards, and would have skewered him had it not knocked him off first. It was a harrowing, harrowing experience.

The most famous harrow in literature comes from Franz Kafka’s story ‘In the Penal Colony.’ The Commander of the colony had devised a machine to carry out sentences imposed on offenders among their own ranks. He not only designed the machine, he was responsible for the organisation of the entire colony. The soldier awaiting sentence had disobeyed the imperative ‘Respect your commanding officer.’ For this he was to be stripped and fixed to the bed of the machine, whereupon its harrow lowered down upon him. Instead of spikes, it had rows of thick, paired needles, a bladed longer one to make an incision, and a shorter tubular one to spray water and rinse away the blood.

It was a writing machine that inscribed the sentence directly upon the body. The accused had not been informed so there was no time to mount a defence, instead, ‘It will be put to him physically.’ The ‘text is traced round the body like a narrow belt; the rest of the body is set aside for decoration.’ The soldier’s wrongdoing begins in tattooed pinpricks and with each pass the blood-inked fangs descend into deeper lacerations, drawing to the ultimate coup de grâce. The sentence is the sentence. The process was slow, taking over twelve hours, so the writing machine was also a torture device, a blanket of pens engraving immense pain before slumping into a shroud.

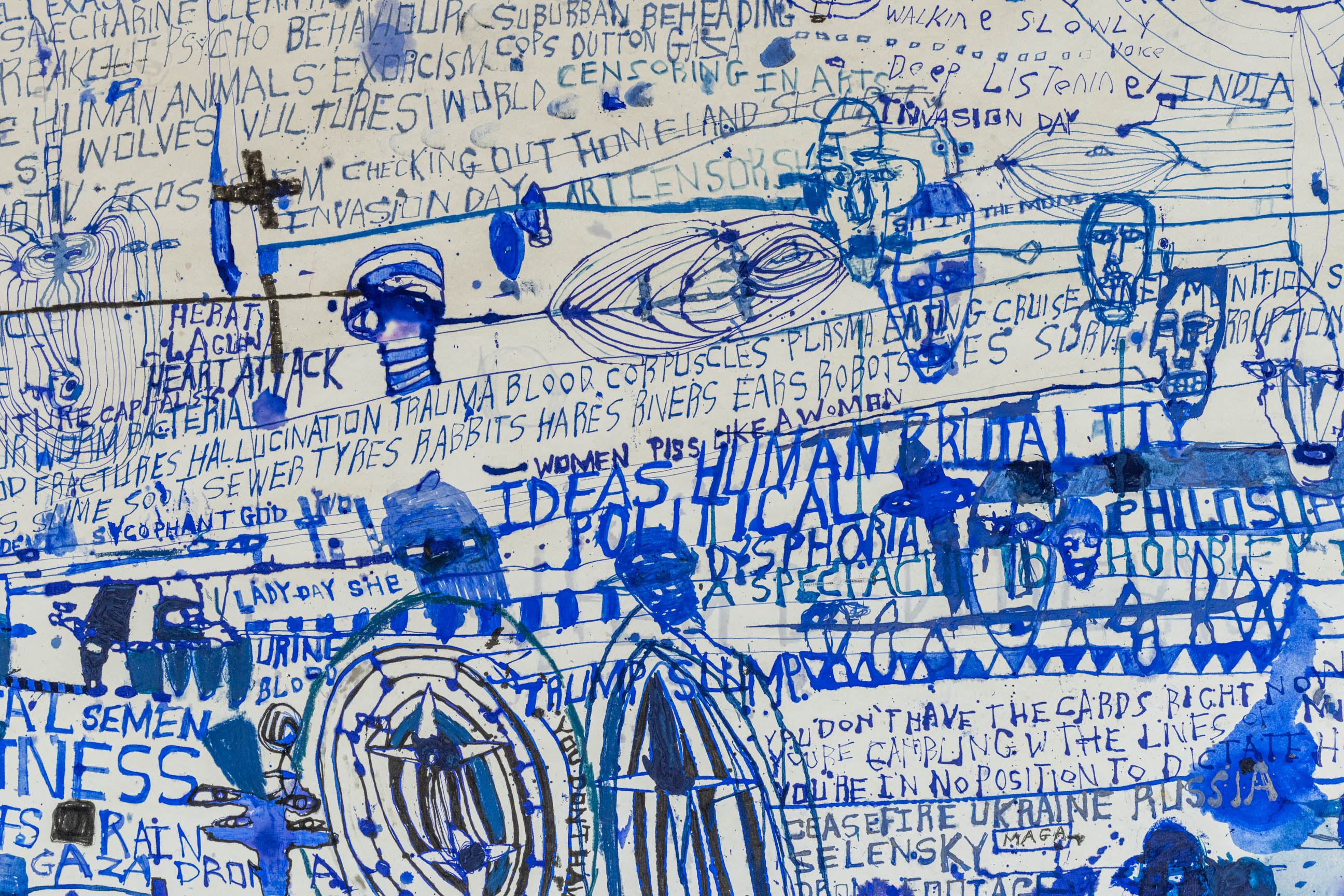

Kafka’s machine was also a media device. The needles were attached to glass so that those gathered could watch and read. It was like a printing press, page by page, body by body, sentence after sentence. Scrolls were once a common transport for writing before codices became books. Scrolls appeared again in huge rolls of newsprint speeding illegibly into the maw of rotating drums, cut and folded with each passing day. Now that books and newspapers are being shelved, a roll out of streaming media sweeps by even more quickly. News breaks amid cycles and spinning that fade at an accelerated pace. Events shed their skins into flooded zones. The light touch with which people scroll their phone dispenses with time, dispenses with people legibly dying on the ground and never covered. Time slips through the palm of the hand under the same glass Kafka fitted to his machine.

Kafka: ‘The harrow follows the human form; here is the harrow for the upper body, here are the harrows for the legs. All there is for the head is this one little spike.’ Now harrows rain in brute surgical strikes that bludgeon and pulverise and leave fields and cities fallow. The sentence in the third book of the scroll commands, ‘Ye shall not make any cuttings into your flesh for the dead,’ yet the proscription fades while cutting into the flesh of others. The Commander dictates: ‘The writing mustn’t be too straightforward; it’s not supposed to be fatal straightaway.’ A declaration unleashes lawlessness that rakes the land of its people, homes, hospitals, schools, and being. Torture must precede the spike aimed at an entire people.

Jones stays with harrowing. Most become numb, their nerves deadening as days and months and months pass and the blood cakes up. But numbness degrades into a compliant soft clay, a callousness as impressionable as wax awaiting a royal insignia. Frame by frame of cinema projects an impression of time into a persistence of vision at breakneck speed. Jones instead holds fast in a persistence of witnessing. England arrests those who wish to witness, Germany mutes them with its own unspeakable. Journalists are targeted and killed, their professional witnessing blocked. Words and images are twisted, wrenched out, and ploughed under. Skulls, faces, and spirits that emerge from the scrolls do so to observe. Their witnessing is an insubordination for which the living must write back.

Jones meets ongoing events with a complex responsiveness and formidable skills flowing forth ceaselessly. What may not be obvious is that Jones often writes and draws his scrolls upside down. It is an uncanny vertical version of Leonardo’s mirror script. The root of scribe is ‘to cut, separate, sift’ and ‘to scratch an outline, to sketch.’ Legible inscriptions and legal and lawless proscriptions have the same root, ‘to gather words, to pick out words.’ In his scrolls, words and images coalesce with the exposed nerves of an empath. They draw upon raw streams of conscience and compassion in an aching beauty of expressionist solemnity.

Douglas Kahn

2025